By Hunter Grove, science and technology reporter

Fralin Hall at Virginia Tech, named for donors William and Ann Fralin. The Fralin name also represents the Fralin Biomedical Research Institute in Roanoke, home to Dr. Ryan Purcell’s lab. Blacksburg, Va. Feb 13 2026

For Dr. Ryan Purcell and his team at Purcell Labs, CRISPR is a key tool for understanding the genetic roots of psychiatric disorders. By engineering neurons with high-risk mutations, including the 3q29 deletion, the lab can see how tiny changes in DNA affect the developing brain, laying the groundwork for future discoveries.

CRISPR, a powerful gene-editing technology, allows Virginia Tech researchers to precisely modify DNA to uncover how it affects neurological disorders such as schizophrenia and autism. At the Fralin Biomedical Research Institute, Purcell and his team engineer human neural cells that mimic high-risk genetic mutations. This process allows them to directly observe how specific DNA changes affect brain development and function. One of the lab’s major projects focuses on the 3q29 deletion, a rare chromosomal region strongly associated with schizophrenia and other neurodevelopmental disorders.

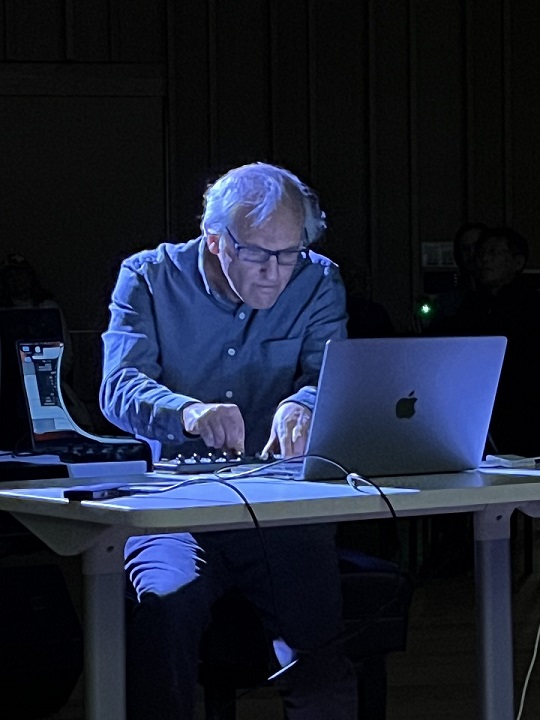

Photo of Dr. Ryan Purcell. Photo by Fralin Biomedical Research Institute

Purcell has been studying the 3q29 deletion since 2017. In late 2025, he was awarded the Seale Innovation Fund, created by Virginia Tech alumni Bill and Carol Seale to support high-risk and innovative biomedical research. The fund provided $275,000 to six projects studying the heart, memory, and mental health.

“We continue to study that in our lab,” Purcell said. “We have a mouse model that we use because they have the same set of genes on their chromosome 16, which is useful when studying the mammalian brain.”

Purcell discovered an interest in neuroscience during classes at Johns Hopkins University but didn’t begin working in psychiatric genetics until his postdoctoral work, when he started studying the 3q29 deletion.

Inside the lab, rows of incubators quietly house developing cells while researchers move between microscopes and computer screens analyzing genetic data. The work unfolds slowly as stem cells are edited with CRISPR and compared with healthy control neurons. The goal is incremental, but the work is transformative, helping build a biological roadmap of psychiatric risk for future research.

Patience and precision are essential. Each experiment builds on the last, helping the team determine what is working and what is not. Answers often take weeks or even years to emerge.

Without CRISPR, the process would take much longer. Its technology allows the team to isolate specific DNA changes much faster than traditional methods such as selective breeding or random mutagenesis. “It’s a major convenience for us,” Purcell said. “We can generate cells that have specific edits to the genome much faster, and it allows us to address questions more efficiently.”

Currently, Purcell Labs is studying the 3q29 deletion and another variant called the 22q11 deletion, which is more common and involves a larger DNA segment. The team is exploring how these deletions affect protein levels and how environmental factors influence outcomes.

“It’s a rare disorder, but we’re still probably talking about 10,000 people in the United States alone, which is a lot,” Purcell said.

Purcell emphasizes that the goal is understanding, not immediate cures. Each experiment adds to a growing foundation for future researchers to explore how genetic changes influence brain function and development. This work could one day guide more effective diagnostics and therapies for psychiatric and neurodevelopmental disorders.

“If we’re able to make progress in our cell culture work, it could translate into people having better outcomes and being able to live more productive, independent, and healthier lives,” he said. “That’s really the long-term goal.”

With continued support from initiatives like the Seale Innovation Fund, Purcell Labs continues to push the boundaries of what CRISPR can reveal about the brain. By modeling the 3q29 deletion in human stem cells and mouse models, his team is uncovering how missing DNA segments disrupt neuron growth, communication, and other cognitive and physical functions. Studying these mutations in detail contributes to shifting psychiatric diagnoses from symptom-based assessments to more biologically informed approaches, helping with early detection, risk assessment, and understanding how these disorders develop.