Category: Arts & Culture

Changing movie theater experiences

by J.J. Hendrickson–

Popcorn popping. Drinks filling. The film reeling. For more than a century, theaters have been a hallmark of American culture.

Now, streaming is changing. The industry and theaters are feeling the impact. Greg Boatwright, general manager of the Lyric Theatre, says it has forced them to partially change their business model.

“In the past, we were primarily a movie theater. We did some special events. We’re now really transitioning away from movies. We now offer more theater classes and put on plays and musicals. So really it’s more about getting the community to use the space however they want.”

Before the pandemic, film stayed in theaters for up to 90 days. Now, some leave them for streaming in as little as 30 or avoid them altogether. This shift is influencing how some movies are made. Virginia Tech’s head of the Cinema Department, Walter Betts, says filmmakers should not rewrite their movies for distracted audiences.

“It’s affecting a lot. Artistic talent is always mangled at any moment in time. It’s never good to be an artist. Be a film artist the way you want it to be. And that probably means you’re not going to be particularly comfortable in a world that says redesign narrative based on people not paying attention to story. That just seems like a weird thing to do.”

As streaming continues to reshape how movies are being made and watched, theaters are working to redefine what the cinematic experience means for their communities.

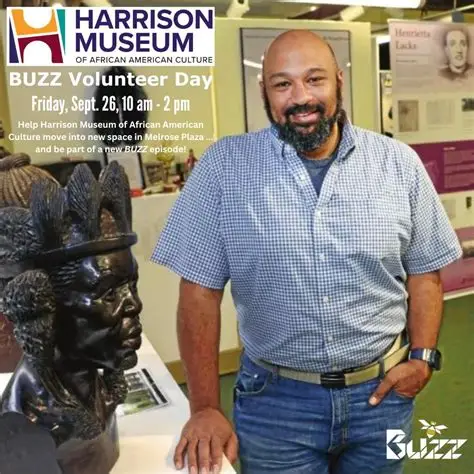

The Harrison Museum Previews Their Temporary Exhibit after Relocating to Their New Location in Melrose Plaza

By Deric Q. Allen, Politics & Government reporter

(Roanoke, Va) — The Harrison Museum of African American Culture had announced their relocation to Melrose Plaza in the latter part of last year. Recently, they announced that they will temporarily open their doors as they launch their “Next 40 Years Campaign.”

The long-established Harrison Museum of African American culture has been a staple of Downtown Roanoke for decades. After their initial move to Downtown Roanoke in 2013, the Harrison Museum will return to Northwest Roanoke in what Executive Director, Eric Beasley, calls a leadership defining move. The museum made the move last summer and aims to enhance Northwest Roanoke’s connection to the region’s cultural ecosystem. This “cultural ecosystem” will be on display in the Harrison Museum’s new thematic exhibits, which will be in rotation every six months. This rotational programming will ensure fresh and relevant content for visitors as well as enlighten them to some of the hidden history of the Roanoke and New River Valley. “We’re moving beyond traditional exhibits to create experiences that link historical objects with the real stories of people’s lives and show how those stories still matter today,” said E.B. Smith.

Eric Beasley is more than the Executive Director of the Harrison Museum, he is a well-traveled Thespian, who’s been introduced to many stories, artists, and histories that traverse the African diaspora. E.B. Smith remarked that, “I think all of that gives you a really nuanced understanding of migration, of how cultural priorities are so nuanced and varied, but also an understanding of how those things tie us together, of course those common threads really can be found regardless of where we’re coming from.”

Smith further commented in an online interview earlier this week, regarding the motives behind the moving of the Harrison Museum and what the local community can expect from the new and improved space. “There was a lot that went in to that discussion, but, when it really boils down I think – the museum had been down at Center of the Square for quite some time, and I think over the last several years in particular the focus of Center in the Square and how it was imagined to show up in terms of the cultural landscape of the city had been shifting. — It was a chance to move back to the neighborhood where the museum was founded, we’re back in the Northwest, so that was really cool to be back in community with folks.”

As the interview progressed, the topic of reparations presented itself, as well as the initiative to distribute potential funds to those affected by urban renewal in Gainsboro and Northeast Roanoke. This project is led by the city’s Equity and Empowerment Advisory Board chair, Angela Penn, and Mayor Joe Cobb. If the reparations effort were to be approved, Roanoke could join other cities such as Charlottesville, Asheville, and Spartanburg in the effort to make up for historical wrongdoing. Although this initiative is progressive, E.B. Smith has differing opinions on what this could mean for the Black community in Roanoke and how the Harrison Museum is contributing to the reparative efforts. “I mean, it’s yet to be seen what reparations and reparative action will look like, it’s not clear if that’s strictly financial, if it’s policy driven, y’know I don’t know what it’s going to look like. But I think all of this work that we do, on some level, is reparative. It’s all about healing, and from my perspective the most important thing that we can do is continue to inspire that imagination about the future.”

In addition to speaking to E.B. Smith, I was also able to set up an interview with Virginia Tech’s Dr. Michelle Moseley, who currently serves as the co-director of the Material Culture MA program alongside her colleague Lauren DiSalvo. Dr. Moseley’s current research projects focus on female collectors and collections and recently published an article titled “At Home in the Early Modern Dutch Dollhouse: Gender, Materiality, and Collecting in the Seventeenth-and Eighteenth-century” while under contract with Amsterdam University Press.

“I haven’t been to the new location yet but I’m aware of the new exhibition on Black community in medical history in Roanoke, which I think is going to be a great one. They do have a lot of photographs, a lot of archives, a lot of papers and these are important records for the community to understand Black History in the New River Valley and the contributions that this community has made to the larger scope of the NRV.” Dr. Moseley has been collecting for several years and has used what she’s collected to answer questions about the people who made them and what their culture is made up of.

To Dr. Moseley, these same questions can be asked and answered when viewing the collections that reside in the Harrison Museum. One archival object that Dr.Moseley is most excited about seeing is the Henrietta Lacks sculpture. Lacks, whose immortal cells are instrumental in the creation of various vaccines and restorative research projects, was a native of Roanoke. Moseley concluded with, “I know the Harrison Museum has had a big hand in promoting that particular work, as you know Henrietta Lacks is from Virginia, so she is such an important person, has such a big impact on our culture and I absolutely can’t wait to see that.”

Local libraries report few book challenges despite national trends

By Aaliyah Kinsler, arts, culture & sports reporter

CHRISTIANSBURG, Va. (Feb. 11, 2026)– Salena Sullivan, Christiansburg Library branch manager, stands between book stacks inside the Christiansburg branch of the Montgomery-Floyd Regional Library. (Aaliyah Kinsler, Newsfeed NRV)

Book challenges and removal requests at public libraries across the New River Valley remain infrequent, even as debates over library collections continue nationally, according to officials with the Montgomery-Floyd Regional Library system.

Library officials say formal requests to reconsider books or materials have been rare locally and have not increased in recent years. This comes despite a growing public attention to book challenges across the country and high-profile cases reported in other parts of Virginia and the United States.

“I’ve been here since 2017, and there have been challenges to the collection, but we certainly haven’t seen an increase over the past few years,” said Montgomery-Floyd Regional Library Director Karim Khan. “It’s infrequent, not something that happens every week or every month.”

Public libraries operate under formal policies and legal standards when evaluating materials rather than responding to individual complaints alone. The Montgomery-Floyd Regional Library system uses a written request for reconsideration process tied to collection development policy, state law and professional library standards that guide how materials are selected, and when necessary, reevaluated.

Library officials say these policies help create consistency and transparency when requests do occur. The system’s collection development policy outlines how materials are selected, how these requests are reviewed, and how final decisions are made. The process usually involves reviewing professional evaluations, collection criteria and community need while making sure decisions remain aligned with legal standards and library ethics principles.

“It’s not a big deal because we’re prepared,” Khan said. “A public library should have policies in place approved by its governing authority. We give our full attention every time somebody puts in a request for reconsideration.”

The library system serves Montgomery and Floyd counties through four branches located in Blacksburg, Christiansburg, Floyd, and Shawsville. Requests must come from people eligible for library cards tied to the service area, which includes local residents, students, and others with qualifying ties to the community. Library officials say this structure ensures the reconsideration process reflects the communities that directly support and fund the library system.

While public discussion often frames book challenges through political or ideological lenses, library leadership in the New River Valley says that the local experiences have been more varied. They say concerns most often focus on perceived content suitability for children or accuracy of factual information rather than a single political viewpoint.

“I think what tends to unify a significant chunk of them is people trying to make sure children are ‘safe,’” Khan said. “It’s either that or, ‘This is scientifically inaccurate.’”

CHRISTIANSBURG, Va. (Feb. 11, 2026)– A “Teen Alley” sign marks the teen section inside a public library, where materials are organized by age groups and audiences. (Aaliyah Kinsler, Newsfeed NRV)

Library officials say many concerns begin as conversations between patrons and staff rather than formal written requests. Front-line employees are often the first point of contact when patrons have questions or concerns about materials, allowing libraries to explain how collections are built and why certain materials are included.

At the branch level, staff say public libraries serve broader roles beyond book circulation, including acting as information centers, study spaces and community gathering spaces for people of all backgrounds.

“Libraries play a very important role in our community as a place where people have access, access to information, access to leisure and access to community,” said Christiansburg Library Branch Manager Salena Sullivan. “It’s one of the only places where you don’t have to pay to be here.”

Sullivan said strong library systems often reflect overall community health, noting that library access often supports education and lifelong learning across age groups.

“Having a robust library in your community is a really good indicator of a healthy community,” Sullivan said.

Library management say public trust plays a significant role in how collections are built and maintained. Officials say collections and programming are designed to meet the needs of different populations across the New River Valley, including families, students, working adults and rural residents with varying information needs and interests.

CHRISTIANSBURG, Va. (Feb. 11, 2026)– Books sit on display shelves inside a Montgomery-Floyd Regional Library branch in the New River Valley. (Aaliyah Kinsler, Newsfeed NRV)

“Libraries’ collections and programming should reflect the needs of the community,” Sullivan said. “We’re here to serve as an information resource.”

Library officials say individuals and families ultimately decide what materials are appropriate for themselves or their children. While libraries organize materials by age group and intended audience, officials say they are not responsible for making individual reading decisions for patrons.

They say legal definitions, particularly around obscenity, are determined by courts rather than library staff. Libraries rely on legal standards and established review processes when evaluating materials rather than subjective personal standards.

“If it’s not obscene according to the law, then it’s not obscene,” Khan said. “It’s a legal term and we are no judge of that.”

Library officials say their goal is to maintain broad access to materials while following professional standards and legal requirements. Officials say public libraries are designed to serve entire communities, even when individual patrons may disagree with certain materials or viewpoints represented in a collection.

Across the New River Valley, library leaders say community relationships and open communication have helped to keep reconsideration requests relatively rare compared to trends reported in some other parts of the country. Officials say continuing conversations with patrons and maintaining transparent processes remain the biggest priorities moving forward.

ARTS/CULTURE: Hidden tunnel linked to Underground Railroad

by JJ Hendrickson & Justin Patrick–

A hidden tunnel was found beneath a dresser in New York City’s Merchant House Museum, which is the only 19th-century home in the city that is preserved intact, both inside and out. The tunnel, which is about 2 feet wide and 2 feet long, could only be revealed by pulling the bottom drawer completely out of the dresser.

The concealed room likely served as a safe house for slaves trying to escape by way of the underground railroad, especially during the early and mid-1800s. White abolitionists were rare in New York at the time the building was constructed in 1832, but it is believed the original owner, Joseph Brewster, was one of the few willing to help slaves find safe refuge.

Does AI write music as well as humans?

Kailey Watson, Arts, Culture and Sports Reporter

Udio, an AI music generator and tool. (Kailey Watson, The New Feed NRV)

Many professionals in the creative technologies field have begun to explore artificial intelligence’s possible utilizations in music, although the scope has yet to be seen.

AI has made its way into seemingly all sectors of life, music being no outlier. Applications like Udio and Suno have arisen to turn written prompts into audible representations at the push of a button. There are positive applications of such software, such as assisting in co-creation and acting as an artistic tool, but there also lies the potential to strip away what some argue music is meant to be about.

Ivica Ico Bukvic has been a professor in Media Arts and Production and the inaugural Director of the Kinetic Immersion and Extended Reality (KIX) Lab at Indiana University since August of 2025. Before this, he worked at Virginia Tech for 19 years and notably is the founder and director of the Digital Interactive Sound and Intermedia Studio and the World’s first Linux-based Laptop Orchestra.

Bukvic also developed L20k Tweeter, which came into being during the Coronavirus pandemic, to bring people together by making music over the internet that could be in sync and co-created. The program encourages collaboration over any distance and differs from the traditional method of the composer and performer.

Bukvic is now looking to infuse the system with an AI co-performer and co-creator to explore how it can create a sense of comfort for those joining the group for the first time. Thus making them feel encouraged to keep playing by feeling less alone.

“Now AI becomes the connecting tissue, rather than something that steals away the creativity from humans,” Bukvic said.

Bukvic is a strong believer in the benefits of creating music, no matter the amount of training one has. “Music was always this thing that was created by humans to bring us together, to celebrate, to enjoy each other’s company, etc.,” Bukvic said. “So if we were to replace that co-creation with something that is generated through AI, in some ways, we are robbing the humanity of the elements that bring us together.”

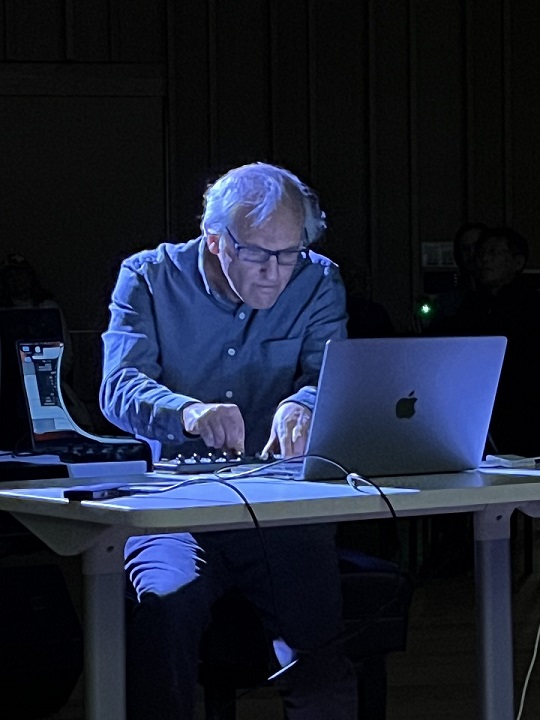

Eric Lyon is a composer, computer musician, spatial music researcher, audio software developer, curator and professor at Virginia Tech. His work with technological applications in music began at a very young age, his first trial being recording himself playing the violin and then playing alongside this recording, a practice not unlike what’s being developed today.

Eric Lyon, performing on the computer. (Courtesy of Eric Lyon)

Amongst his many compositions, Lyon also researches ways to enhance music technologies, including publicly available software FFTease, written with Christopher Penrose, and LyonPotpourri, collections of externals written for Max/MSP and Pd.

A survey by Qodo, an AI coding platform, reported that 82% of software developers use AI coding tools daily or weekly, but 65% say it misses relevant context during critical tasks. A similar sentiment is shared by Lyon.

“I haven’t gotten to the point where I could coach the audio programming to be as good as the kind of code that I wrote 25 years ago,” Lyon said. However, he expects it to be within five years based on the strides that it is continually making.

AI has a ways to go in music composition as well. Lyon shared an example where he asked a music AI, either Udio or Suno, to write a song about the atomic bomb. The result was a cheerful tune about nuclear war, not particularly befitting for the subject matter, but something that he shared he would never have been able to come up with. A snippet of the song would become part of a piece of his.

As these AI tools stand now, Lyon noted, they do not make very good music on their own. An example he shared was of an AI that was trained on every Beatles song, and then asked to create the next 50 Beatles songs. The result was mediocre, “Not even close to the worst Beatles song,” Lyon shared. This being said, it’s unclear how AI will continue to progress, and if it is possible for this threshold for good music to be reached.

There are already AI musicians breaching into platforms like Spotify, but whether this will become the future is yet to be known. Lyon argues that there has always been a deskilling aspect to music, such as how all keyboardists used to know how to read figured bass. AI could be another step in removing areas of knowledge that are no longer seen as necessary. An extreme would be that no one has the skills to compose a piece, and music is generated simply by the push of a button.

“AI is kind of an amputation, but it feels a little bit more like brain surgery,” Lyon said.

Bukvic begs the question, “Why would you use AI to remove what was the, arguably, primary motivation for having such an activity in place in the first place?” He instead looks to the notion of co-agency, a concept in which he currently has pending projects.

He aims to develop his own AI collaborator that is trained on important parameters to assist in the process of co-creation. He shares that it could assist in live performances, as there are only so many things one can juggle in one’s mind at once, and only so many hands to carry out said things.

Lyon’s AI-related projects are titled “Eric, this is so you coded,” a whole piece coded by AI, and “How I learned to stop worrying and love the hallucinations,” a work about how AI malfunctions and gives false information. Lyon shared his goal with this piece is to answer the question, “How can you make AI worse rather than better in ways that are artistically interesting?”

AI certainly has applications in music, though whether its trajectory lies in assisting artists or becoming them will be answered with time.

“How do you create a Beethoven and then make that Beethoven make music?” Lyon said. “I mean, we’ve got 32 piano sonatas. If you could make a Beethoven and you could get 32,000, would they all be as great?”

How Virginia Tech curates the voices that take the stage

By Aaliyah Kinsler, arts, culture, and sports reporter

Margaret Lawrence, Director of Programming for the Center for the Arts at Virginia Tech. Photo Courtesy of Rob Strong and Virginia Tech

As universities face increasing questions about representation, audience engagement and institutional responsibility, arts programming has become a large reflection of broader cultural values.

At Virginia Tech, the Center for the Arts brings professional performers from around the world to campus stages and shapes how students and the New River Valley community encounter the arts.

In an interview, Margaret Lawrence, director of programming for the Center for the Arts, discussed how those decisions are made, how audiences influence programming and why representation matters.

Her comments were edited slightly for length and clarity.

How does Virginia Tech and the Center for the Arts decide which artists and performers are featured on campus?

I can only speak for the Center for the Arts, because of course there’s lots of other stuff happening in the arts on this vast campus. We are really the center for bringing professional American and international touring performing artists, and top-notch professional visual artists.

I’m the person involved with performing artists specifically. We produce a series of between 25 and 30 performances each year, kind of balanced between the two semesters. We don’t really present much in the summer when the students aren’t here.

Our mission is to really bring the most extraordinary arts experiences here and to celebrate the diversity of kinds of art forms, of kinds of artists, of individuals. This might be the only chance a student at Virginia Tech has to see a full philharmonic orchestra, or a contemporary American dance company, or a very famous jazz artist they’ve heard of but never saw in person. This is a really formative time for students here.

What goes into deciding which artists make it into a season?

I’ve been a curator for more than 40 years. I have a lot of knowledge of the artists who are out there, not only in the U.S. but across the globe, and a lot of networks in the field with other performing arts centers.

What we try to bring together are some artists who are at the top of their game and very well known, and then artists who are emerging, who you may never have heard about. That proximity to those artists and their work is really exciting.

We’re just as interested in presenting really important music of the past as we are in premiering brand-new compositions. We even helped commission a brand-new piece that premiered here by a living composer.

Do artists reach out to you, or do you reach out to them?

All of the above. Almost all professional artists are represented by agents and management companies. They know who I am. I often pursue somebody for years before it finally comes true.

I might be in New York and have a whole bunch of meetings. We had a trio here recently that was a new project. Those artists thought of it and put it together. The minute I heard about it; I was pursuing it.

Some artists are incredibly expensive to bring, and it might take years and really creative thinking to raise the funds. When we brought Yo-Yo Ma here, the cellist, that didn’t happen overnight.

How much influence do students and community members have in programming decisions?

I’m working for at least a year and a half in advance. Right now, I’m almost done programming 2026–27, and I’m starting to work on 2027–28. That automatically changes how we approach things.

If I only brought artists that I personally love, some of those things are really esoteric. That doesn’t mean I’m going to bring it to Blacksburg. So, I try to create a real balance.

We do national touring Broadway shows because people want to see them. We see people there we might not see at any other kind of performance. That’s really important to us.

Do engagement and education factor into programming choices?

We’re not only presenting performances. We’re creating what we call engagement activities. We ask artists to do workshops, come into classes, teach master classes and do school-time matinee.

For some kids, it might be the first time they’ve ever been to a theater. Those experiences are incredibly important for showing people what the world around them is.

Have you noticed shifts in audiences over time?

We’ve built a very strong subscription base from the community. Many of them will sign up for the entire season and trust us to have a great experience.

The student percentage of attendees is very healthy. It tends to be around 23% of the audience, which is quite high. I think that’s partly because we do so much engagement with the artists.

Have any performances sparked reflection about whose voices are being elevated?

Several years ago, we brought a trans theater artist from London who did a piece about their identity. People told me, “You never would have seen a piece like this when I was a student here.”

For students and community members, it creates a sense of belonging. For everybody else, it’s about learning about the people we share this globe with.

We also brought a dance company from India collaborating with a company from Sri Lanka. A student told me it was the first year they were able to form a Sri Lankan student organization. The artists were from her hometown. Seeing that on the stage here was incredibly powerful.

Looking ahead, how should Virginia Tech continue evolving in how it presents artistic voices?

The arts are about entertainment, but they’re also about truth and self-expression. College is when people are figuring out what they stand for and what’s important to them.

The more arts we have on campus, whether through the Center for the Arts or elsewhere, the better.

Helping good music live on: Geoff White on music of the Civil War

By Kailey Watson, Arts, Culture and Sports reporter

Geoff White, musician and historian. (Courtesy of Geoff White)

Geoff White is a lifelong musician whose talents found their calling in Civil War-era music. Through reenactment events and lectures, White shares tunes of the time with all who will come to listen.

After moving to Virginia in 2007, he and his wife began participating in civil war reenactments. White brought his fiddle, and his journey began by wanting to have more songs to play around the campfire. He would later receive a Bachelor’s in History in 2013 from Radford University, where he was employed, and worked on studies dealing with music from the Civil War. From there, White began performing combined concerts and lectures from battlefields to retirement homes.

The following questions and answers were edited slightly for length and clarity.

How do you find the Civil War-era songs that you’re playing?

The Civil War was a unique period in history because so many of the people who fought it from the bottom up, the privates and the rankers, were literate. So we had this explosion of literacy, people being able to write letters and diaries and accounts, but you also have that same thing with musical literacy. Music was much more for the masses, and not just passed down through the oral tradition.

As far as what we call Parlor Music, a lot of that is readily available. Another avenue would be the music that was printed and distributed to the musicians who were in the army. You also had people going around documenting and recording what musicians were playing. In some cases, it can be very difficult to find just how old this tune is or how new this tune is.

There’s also another avenue, which would be during the Depression. The Works Progress Administration went around to people who were former slaves and said, we need to document what these people have to say about the lives they led before nobody is alive who remembers it at all. They’re what we call the slave narratives.

In some cases, they also had people singing songs that they actually recorded with a tape recorder. They were very, very young when these things were happening. But at least they have primary sources.

Have you noticed any difference in being able to find music from one side or the other?

No, I don’t think there’s any sort of difficulty on one side or the other. There’s plenty available on both sides, or neutral. Just songs that both sides enjoyed, because when it comes down to it, it’s Americans fighting Americans.

As far as picking and choosing, I try to present songs from both sides of the war. Not to express any sort of bias or sentiment towards one side or the other, but to put it in a historical context.

What were these songs typically about?

It could be about anything, because these soldiers were people. They were normal, common people.

Sometimes they’re singing about battles. There was an old song called “The Mockingbird,” where the soldiers repurposed it to be about the siege of Vicksburg, and they’re talking about the parrot shells whistling through the air.

There are a lot of songs about food. I mean, it’s fundamental for existence, right? So why not sing about food? You had songs about the beans that they ate, or about goober peas.

There’s love, like Lorena, a song about a lost love.

I thought about this a lot when the pandemic happened. There was this sentiment that I heard over and over again. It was, “when this is over.” When the pandemic’s over. There was a refrain and a civil war song, “when this cruel war is over, when this war is over,” there’s always this, let’s just get past this. So there was a sentiment that I’ve seen and sort of experienced when we went through this life-changing, traumatic event of the pandemic.

They were looking back or saying, this sucks. We want to look ahead. You know, to win, so all this crap is done.

It was a very hyperbolic time. It was a time when people spoke and wrote very passionately about what they were experiencing. So you see that reflected in a lot of the media and in the books and the literature and, of course, the music. You know, they were wax poetic in a way that we don’t do exactly right now about anything and everything under the sun.

For your lectures and events, do you speak solely about the history of the songs, or do you also include general history?

I’m talking about the history of the song, but in some cases, the song has a story to tell beyond just who wrote it, when it was about and what was happening in the world.

I do a tune called the Spanish Waltz, which you might have heard at West Point. The education for these up-and-coming officers was not just to be an officer. These men were expected to move through the higher echelons of society without embarrassing themselves, their unit and the US Army. They were trained how to eat properly at a formal dinner. How to dance properly.

There might be a problem that you foresee when you have a single sex school. How do you teach the men to dance? Well, half the men have to wear an armband, so they learned the ladies’ part of the dance. And so that’s an interesting way of thinking about what it would have looked like then at the US Military Academy. I use the Spanish Waltz as a way of talking about that. Now I’m going to play the Spanish Waltz, and you can let your imagination run wild.

What is the importance of keeping the music of this time alive?

My first response is, just because it’s good music. I don’t want to see that die on the vine. These songs and these musicians deserve to be remembered in some way.

Another thing is that when we learn about the Civil War in a very immersive environment, like a reenactment, one of the things that helps contribute is hearing the music. That can help transport you back in time, just like going to the symphony and hearing Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony can transport you back to when people were listening to that kind of music.

It’s one thing to read about history. It’s another thing to smell history right at a reenactment, and holy cow, well, you smell history. You can taste history. You can hear history when talking about the music. So that’s my stock and trade, hearing history.

ARTS/CULTURE: Music and Arts in Social Media

By: Conner Parker and Evan Niewoehner —

In today’s social media revolution, opportunities have opened for those who are unseen. Small-scale artists can share their work internationally with millions of viewers. A teenager with a hobby for music or a father painting out of his garage could become an internet sensation at any time.

From Alex Warren to Max Alexander, artists are finding their voices and success through social media. Posting one’s art can now lead to a full-time career in creative fields.

In this podcast, Evan Niewoehner and Conner Parker discuss the changing environment of artistic careers. They cover social networks, creative strategy, and monetization, all of which are impacted by social media’s growth.

Virginia Tech’s Center for the Arts showcases new exhibit “Things I Had No Words For”

By Zoe Santos, arts, culture, and sports reporter

BLACKSBURG, Va. (Sept. 11, 2025)– Artists Clare Grill and Margaux Ogden converse in front of one of Grill’s paintings. (Zoe Santos, Newsfeed NRV)

Visitors gathered Sept. 12 at the Center for the Arts at Virginia Tech for Beyond the Frame, a monthly tour series that gives audiences a closer look at current exhibitions. September’s tour focused on “Things I Had No Words For”, featuring the paintings of Clare Grill and Margaux Ogden.

Beyond the Frame takes place on the second Thursday of each month at noon. The program invites audiences into the galleries for informal conversations about the art on display. This fall’s exhibitions, which opened Sept. 4 and run through Nov. 22, include Grill and Ogden’s “Things I Had No Words For” on the first floor and “Seeing and Reading” featuring Dana Frankfurt and Josephine Halberstam, upstairs.

The exhibition is part of CFA’s rotating series of gallery shows, which change out each semester. Visitors can view the works during regular gallery hours, Tuesday through Friday, 10 a.m.- 5 p.m., and Saturday, 10 a.m.- 4 p.m.

BLACKSBURG, Va. (Sept. 11, 2025)– Margaux Ogden, Clare Grill, and Brian Holcombe discuss one of Ogden’s pieces on display. (Zoe Santos, Newsfeed NRV)

Curated by Brian Holcombe, director of the visual arts program, “Things I Had No Words For” pairs Grill’s contemplative canvases with Ogden’s energetic, color-driven abstractions. Holcombe said he was first introduced to the two artists in 2014 through a mutual friend and immediately saw their work as complementary. “It struck me that they would have a wonderful conversation together,” Holcombe said during the gallery tour.

Clare Grill, lives and works in New York, received her Master’s of Fine Arts from the Pratt Institute in 2005, according to her biography on M + B’s website. She builds her work from a personal archive of images, memories, and textures. Her paintings often incorporate faint outlines and muted tones that evoke a sense of layers of history. She told the group that she begins with fragments from the past, mostly from antique embroidery, and allows them to inspire her to create something new on the canvas.

“I really think of painting as an excavation,” Grill said, “I’m looking for something, and I’m not exactly sure what it’s going to be until I’m there.”

BLACKSBURG, Va. (Sept. 11, 2025)– Artist Margaux Ogden poses for a photo in front of one of her pieces on display titled “Bathers.” (Zoe Santos, Newsfeed NRV)

Ogden, who is based in Brooklyn, uses a very different process. Her works are full of bright colors and geometric shapes, and she paints without sketches or strict plans. She explained that her studio workflow thrives on risk and spontaneity. All of her pieces are seemingly perfectly symmetrical, but she shared with the group that she only measures the first four lines of a painting and then relies on her judgment for the rest. “The way I work is improvised,” Ogden said. “It’s not predetermined. It’s about responding in the moment.” View more of Ogden’s works here.

Holcombe said bringing both artists into the same gallery space emphasizes the contrasts while also showing how abstraction can take multiple forms. “Clare is often working from history, while Margaux is responding to the present moment,” he said. “That tension is what makes this exhibition really exciting.”

The gallery tour drew a mix of students, community members, and regional art enthusiasts. Among them was an older couple who had travelled from Roanoke specifically for the event.

As Holcombe guided visitors through the space, the group moved slowly between large canvases that filled the white-walled gallery. Grill’s pieces provoke close looking, with texture and subtle brushstrokes that reveal themselves the longer you look at the piece. Ogden’s paintings, in contrast, catch viewers’ attention immediately with bright bursts of pink, green, and orange.

Standing in front of one of Ogden’s pieces, Holcombe described the effect of viewing both artists side by side, “There’s an energy in the room when you put these two bodies of work together,” he said. “You start to notice connections you wouldn’t see otherwise.”

Beyond the Frame and “Things I Had No Words For” continues CFA’s mission to showcase contemporary art while engaging both the campus and surrounding communities. Previous exhibitions have included national and international artists, but Holcombe emphasized the importance of highlighting painters like Grill and Ogden, who are contributing to ongoing conversations in abstract art today.

Both artists spoke about the balance between personal meaning and public reception in their work. Grill said she hopes viewers bring their own experiences to her paintings rather than looking for a single interpretation. “I want the work to feel open, like there’s room for the viewer to enter,” she said.

Ogden shared that thought, noting that the intensity of the color often provokes strong reactions. “People might see joy, chaos, or even confusion,” she said. “All of that is valid. It’s about how the painting meets you.”

For visitors, the tour was not only about viewing paintings but also about connecting with artists and ideas. Some lingered after the formal program ended, continuing to talk with Grill and Ogden about their processes. A few students took notes, while others snapped photos to remember specific works.

The CFA hopes that kind of engagement continues throughout the fall. With the exhibition open until Nov. 22, Holcombe encouraged visitors to come back more than once, noting that abstraction often rewards repeat viewings.

“You can walk into this show on different days and notice new things each time,” he said. “That’s the beauty of work that resists easy answers.”

“Clare Grill and Margaux Ogden: Things I Had No Words For” is on display at the Center for the Arts at Virginia Tech through Nov. 22. Admission is free. More information is available on the Center for the Arts at Virginia Tech’s website.