Kailey Watson, Arts, Culture and Sports Reporter

Udio, an AI music generator and tool. (Kailey Watson, The New Feed NRV)

Many professionals in the creative technologies field have begun to explore artificial intelligence’s possible utilizations in music, although the scope has yet to be seen.

AI has made its way into seemingly all sectors of life, music being no outlier. Applications like Udio and Suno have arisen to turn written prompts into audible representations at the push of a button. There are positive applications of such software, such as assisting in co-creation and acting as an artistic tool, but there also lies the potential to strip away what some argue music is meant to be about.

Ivica Ico Bukvic has been a professor in Media Arts and Production and the inaugural Director of the Kinetic Immersion and Extended Reality (KIX) Lab at Indiana University since August of 2025. Before this, he worked at Virginia Tech for 19 years and notably is the founder and director of the Digital Interactive Sound and Intermedia Studio and the World’s first Linux-based Laptop Orchestra.

Bukvic also developed L20k Tweeter, which came into being during the Coronavirus pandemic, to bring people together by making music over the internet that could be in sync and co-created. The program encourages collaboration over any distance and differs from the traditional method of the composer and performer.

Bukvic is now looking to infuse the system with an AI co-performer and co-creator to explore how it can create a sense of comfort for those joining the group for the first time. Thus making them feel encouraged to keep playing by feeling less alone.

“Now AI becomes the connecting tissue, rather than something that steals away the creativity from humans,” Bukvic said.

Bukvic is a strong believer in the benefits of creating music, no matter the amount of training one has. “Music was always this thing that was created by humans to bring us together, to celebrate, to enjoy each other’s company, etc.,” Bukvic said. “So if we were to replace that co-creation with something that is generated through AI, in some ways, we are robbing the humanity of the elements that bring us together.”

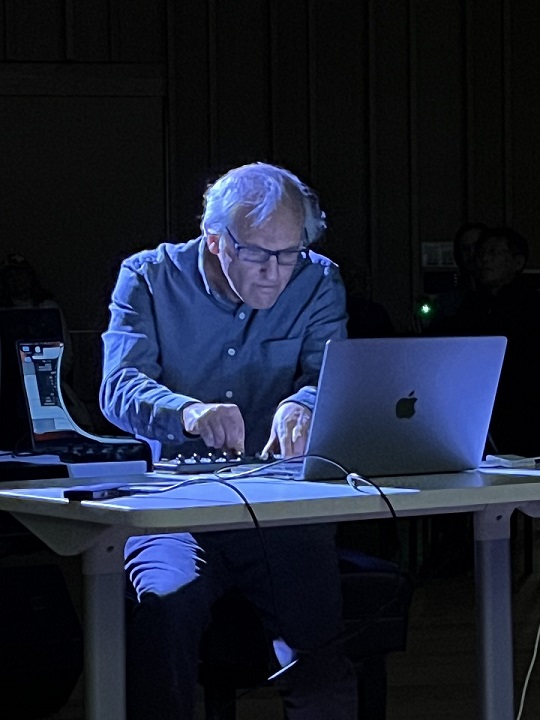

Eric Lyon is a composer, computer musician, spatial music researcher, audio software developer, curator and professor at Virginia Tech. His work with technological applications in music began at a very young age, his first trial being recording himself playing the violin and then playing alongside this recording, a practice not unlike what’s being developed today.

Eric Lyon, performing on the computer. (Courtesy of Eric Lyon)

Amongst his many compositions, Lyon also researches ways to enhance music technologies, including publicly available software FFTease, written with Christopher Penrose, and LyonPotpourri, collections of externals written for Max/MSP and Pd.

A survey by Qodo, an AI coding platform, reported that 82% of software developers use AI coding tools daily or weekly, but 65% say it misses relevant context during critical tasks. A similar sentiment is shared by Lyon.

“I haven’t gotten to the point where I could coach the audio programming to be as good as the kind of code that I wrote 25 years ago,” Lyon said. However, he expects it to be within five years based on the strides that it is continually making.

AI has a ways to go in music composition as well. Lyon shared an example where he asked a music AI, either Udio or Suno, to write a song about the atomic bomb. The result was a cheerful tune about nuclear war, not particularly befitting for the subject matter, but something that he shared he would never have been able to come up with. A snippet of the song would become part of a piece of his.

As these AI tools stand now, Lyon noted, they do not make very good music on their own. An example he shared was of an AI that was trained on every Beatles song, and then asked to create the next 50 Beatles songs. The result was mediocre, “Not even close to the worst Beatles song,” Lyon shared. This being said, it’s unclear how AI will continue to progress, and if it is possible for this threshold for good music to be reached.

There are already AI musicians breaching into platforms like Spotify, but whether this will become the future is yet to be known. Lyon argues that there has always been a deskilling aspect to music, such as how all keyboardists used to know how to read figured bass. AI could be another step in removing areas of knowledge that are no longer seen as necessary. An extreme would be that no one has the skills to compose a piece, and music is generated simply by the push of a button.

“AI is kind of an amputation, but it feels a little bit more like brain surgery,” Lyon said.

Bukvic begs the question, “Why would you use AI to remove what was the, arguably, primary motivation for having such an activity in place in the first place?” He instead looks to the notion of co-agency, a concept in which he currently has pending projects.

He aims to develop his own AI collaborator that is trained on important parameters to assist in the process of co-creation. He shares that it could assist in live performances, as there are only so many things one can juggle in one’s mind at once, and only so many hands to carry out said things.

Lyon’s AI-related projects are titled “Eric, this is so you coded,” a whole piece coded by AI, and “How I learned to stop worrying and love the hallucinations,” a work about how AI malfunctions and gives false information. Lyon shared his goal with this piece is to answer the question, “How can you make AI worse rather than better in ways that are artistically interesting?”

AI certainly has applications in music, though whether its trajectory lies in assisting artists or becoming them will be answered with time.

“How do you create a Beethoven and then make that Beethoven make music?” Lyon said. “I mean, we’ve got 32 piano sonatas. If you could make a Beethoven and you could get 32,000, would they all be as great?”